Efficient Disk concurrency through eio

Pre-requisite knowledge assumed: OCaml

—

Getting concurrency right is often tricky. Recently, I’ve been playing around with eio, an IO concurrency library for OCaml. In particular, I was inspired by a discussion post asking how to implement an efficient directory copy using eio. The post attracted many suggestions and I was curious to understand which optimizations benefits eio the most. Turns out, this problem was a one-way ticket down the rabbit hole… Here’s how it went!

Concurrency

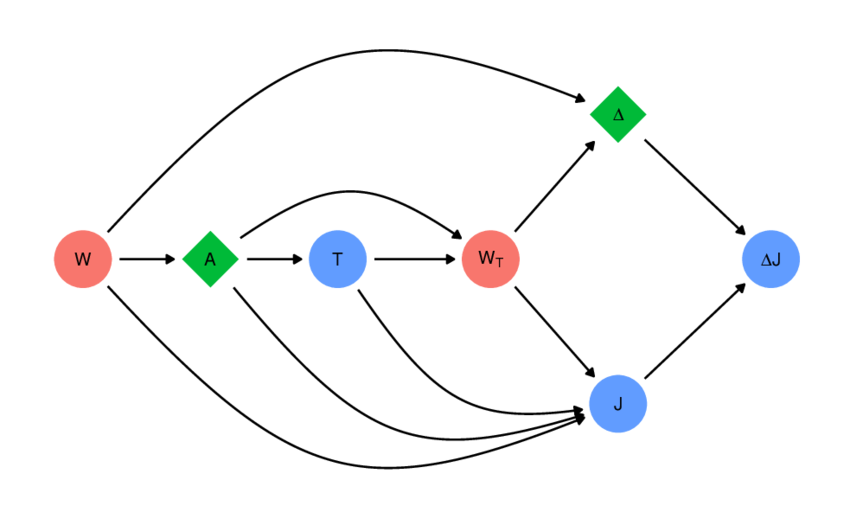

To get our definitions straight, we’ll define concurrency as the structuring of a program into separate independent tasks. Each task runs one at a time but can be interleaved with one another. However, this overlapping structure doesn’t provide any speedup on it’s own. It needs to be paired with a workload that consists of some waiting on some slow device IO and other independent work that could be processed in the meantime. To give a concrete example, a concurrent way to write to two files to disk would be:

t1: Write to file A

t2: While waiting for write to A to complete ... | Write to file B

t3: While waiting for write to B to complete ... | Writing to file A completes

t4: Writing to file B completes

Overview of backends concurrency models

In order to enable concurrency, modern operating systems provide two asynchronous IO models to pick from: readiness-based IO and completion-based IO.

Readiness-based IO, is provided through the use of non-blocking file descriptors. Such descriptors respond in one of two ways when IO is requested on them. If data is ready to be consumed, then the request is processed as per usual. If data is not yet available, the request returns immediately with an error code to indicate this so that the process returns to check again later for data.

Completion-based IO in contrast, is accomplished by using specific asynchronous API’s which hand-off IO requests entirely to the OS and returns immediately. Internally, this typically involves requests being queued and monitored by an external kernel thread to process them in a separate execution context. Upon completion the data, the OS is responsible for notifying the requesting process.

Recognizing when to use one or the other is subtle but worth thinking about. Primarily, readiness-based IO only guarantees that the program will not block on IO but have unpredictable latency. If not properly accounted for, programs could end up handling an arbritrary long requests on ready file descriptors, thus causing poor latency. On the other hand, completion-based IO is more predictable in this regard since requests are handled outside of the process execution. However this model generally has lower throughput since requests now have to be threaded through the OS.

eio

The eio library exposes high-level structured concurrency constructs for programming with asynchronous IO. Eio’s main abstraction are Fiber’s which are programmatic way to express independent threads of work. Eio currently supports running on 3 systems, windows, posix and linux. In order to push performance as far as we can, we’ll focus on linux which is based on io-uring, a sophisticated and fast backend based on completion-based IO.

Gotchas!

Before we can dive into any optimizations, here are some immediate gotchas to keep in mind.

write: not as slow as you’d think

Those with experience programming with non-blocking IO may have realized

that we’re stepping into an exceptional case. Our copy directory problem

works with regular files and the man pages for open (2) state:

O_NONBLOCK or O_NDELAY

“Note that this flag has no effect for regular files and block devices;

that is, I/O operations will (briefly) block when device activity is

required, regardless of whether O_NONBLOCK is set.”

Well, this seems like an obvious win for us at the completion based IO

camp. However, this leaves out several important details. In particular,

O_NONBLOCK doesn’t work for regular files because writes go directly to

the page cache. Making many individual small requests for IO (in our case - to disk)

is extremely expensive. To guard against this, kernel developers implement

an efficient mechanism to transparently batch write’s into a bigger

request that is later flushed to disk. The man pages for write (2)

confirms this behaviour

A successful return from write() does not make any guarantee that

data has been committed to disk. On some filesystems, including

NFS, it does not even guarantee that space has successfully been

reserved for the data. In this case, some errors might be

delayed until a future write(), fsync(2), or even close(2). The only

only way to be sure is to call fsync(2) after you are done

writing all your data.

As a consequence, a call to write does not suspend because it is readily able to write data into the page cache. Since our copy problem is not concerned with latency, issuing sequential writes end up being quite efficient because the program doesn’t need to wait. The only time a write may block is when there are no free pages left and dirty pages are flushed to disk to reclaim space. Though in practice, this behaviour is usually not an issue.

All of this context was provided to now circle back to how io-uring handles this. As described, using completion-based IO to perform writes can be less performant than the sequential version because of the extra infrastructure required to handle queued requests. io-uring is designed to make smarter choices about IO and does not purely queue request. If uring notices that an IO operation can be completed immediately (e.g. write to a page cache), it will do so inline instead of generating an async request for it. Conversely, if a write needs to be suspended, it then adds it to the async queue. This hybrid architecture gives us the best of both worlds for regular file IO. If so desired, a uring request can be set to always generate an async request if low latency is required.

This discussion is not complete without mentioning the implications on

persistence. Having peered into the implementation, we now realize that

the OS may lie to us about having written something to disk. For certain

applications, this can be detail is important to have some gurantees about

their programs semantics if a failure occurs. The way to ensure that

a write has made it to disk is the call fsync which forces dirty pages

to be written to disk. This may or may not be a required property of real

programs so our benchmarks will consider both cases.

read: faster than expected

Following the discovery that regular files are blocking, surely reading files will be slow since there is no way around having to fetch data from disk. This is true, but the kernel has other tricks up it’s sleeve. When requesting data for files, the kernel performs a “readahead” optimization. As the name indicates, the kernel prefetches more data into main memory than the program had asked for. This way, future reads are more likely to hit cache rather of requiring a disk transfer at every read. Even better, some applications are designed to work with data read once into memory and are kept around to be reused directly from RAM. From a benchmarking perspective, we should also include this in our test using a hot and cold page cache.

Baseline Expectations

It’s useful to first get some idea of the theoretical throughput of the system.

Hardware Capabilities

The disk on my machine is the Intel Pro 6000p NVMe PCIe M.2 512GB. I couldn’t find information about the transfer rates on the spec sheet so I used public benchmarks of random mixed read write transfers which came out as 40.9 MB/s. ref

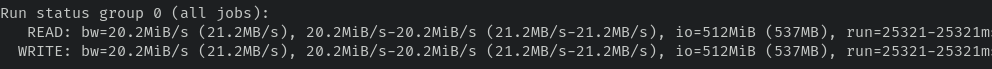

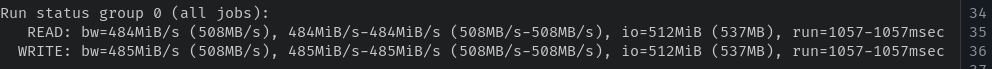

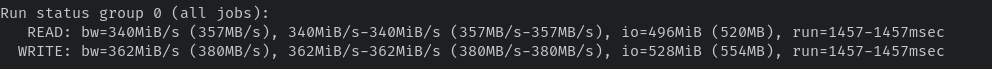

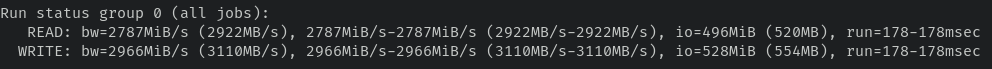

Measurements with fio

Now to check where we are at on my machine, I used the fio benchmarking

tool to measure the throughput of random read writes.

fio --name=expect_fsync+cold --rw=randrw --size=1GB --end_fsync=1 --invalidate=1

It’s also worthwhile to simulate workloads that benefit from caching and doesn’t require hard guarantees on disk writes since some applications fall in this category.

fio --name=expect --rw=randrw --size=1GB --pre_read=1

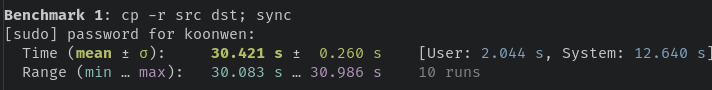

Workload expectations

The above results measure the raw IO throughput to disk that will serve as

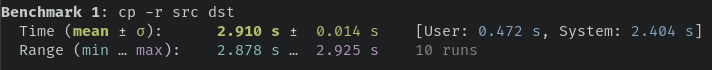

our upper bound. We’ll now use hyperfine against the system cp -r

command on a synthetic filesystem to get a baseline for the algorithm. The

filesystem properties are:

Directory depth: 5

Files per directory: 7

Filesize: 4k

Num files: 97655

Total size of IO = 480MB (R) + 480 (W) = 960MB

Our estimated throughput for cp -r is therefore:

fsync+cold cache: 960MB / 30.421 = ~32MB/s

regular: 960MB / 2.910s = ~330MB/s

We’re right around the ballpark of the results of the fio workload.

Can we do better?

Looking into how cp is implementation, it doesn’t employ any concurrency

and just performs a sequential walk through the directory using a blocking

syscalls. Remembering that read/writes are fast due to readahead and write

buffering, we’d guess that the sequential version may do better than the

concurrent version on workloads without “fsync + cold cache”. This is

because in actuality it spends little time waiting. With that

configuration on however, the sequential version starts suffers from long

suspension and the concurrent one really shines

Copy algorithm in eio

Let’s look at the following algorithm taken from that post

open Eio

let ( / ) = Eio.Path.( / )

let copy src dst =

let rec dfs ~src ~dst =

let stat = Path.stat ~follow:false src in

match stat.kind with

| `Directory ->

Path.mkdir ~perm:stat.perm dst;

let files = Path.read_dir src in

List.iter (fun basename -> dfs ~src:(src / basename) ~dst:(dst / basename)) files

| `Regular_file ->

Path.with_open_in src @@ fun source ->

Path.with_open_out ~create:(`Exclusive stat.perm) dst @@ fun sink ->

Flow.copy source sink;

| _ -> failwith "file type error"

in

dfs ~src ~dst

let () =

Eio_linux.run (fun env ->

let cwd = Eio.Stdenv.cwd env in

let src = cwd / Sys.argv.(1) in

let dst = cwd / Sys.argv.(2) in

copy src dst)

The above implementation is a minimal sequential version of cp -r using

eio’s API’s. However, right now we don’t expect to do better and in fact,

a quick time shows that this implementation takes 8.8 seconds to

complete, the throughput is only 109MB/s. 3 times slower than the

regular cp. We will rack up this extra overhead as the cost of running

the concurrency infrastructure in a sequential manner for now.

To make this program concurrent, the simple change would be to spawn new fibers to handle each file to copy.

- List.iter (fun ...)

+ Fiber.List.iter ~max_fibers:2 (fun ...)

Though the problem with this method is that we have not much control on the total number of fibers spawned. This is problematic for two reasons. The first is that fibers have their own contexts and thus maintaining it is extra memory space. Secondly, there is a limit on the number of open file descriptors a process is allowed to have open. Looking at this program, it is implemented with DFS. If the filesystem we are attempting to copy is big enough, we could easily burst the limit on the number of open file descriptors. It’s therefore neccessary to throttle the number of fibers we spawn.

Copy revised

Our new version is structured using BFS in order to prevent holding file descriptors open during the recursion in DFS. Additionally, it also uses a semaphore to control the total number of fibers the program can spawn at any time.

module Q = Eio_utils.Lf_queue

let copy_bfs src dst =

let sem = Semaphore.make 64 in

let q = Q.create () in

Q.push q (src, dst);

Switch.run @@ fun sw ->

while not (Q.is_empty q) do

match Q.pop q with

| None -> failwith "None in queue"

| Some (src_path, dst_path) ->

begin

let stat = Path.stat ~follow:false src_path in

(match stat.kind with

| `Directory ->

Path.mkdir ~perm:stat.perm dst_path;

let files = Path.read_dir src_path in

(* Append files in found directory *)

List.iter (fun f -> Q.push q (src_path / f, dst_path / f)) files

| `Regular_file ->

Fiber.fork ~sw (fun () ->

Semaphore.acquire sem;

Path.with_open_in src_path @@ fun source ->

Path.with_open_out ~create:(`Exclusive stat.perm) dst_path @@ fun sink ->

Flow.copy source sink;

Semaphore.release sem

)

| _ -> failwith "Not sure how to handle kind");

end

done

Results

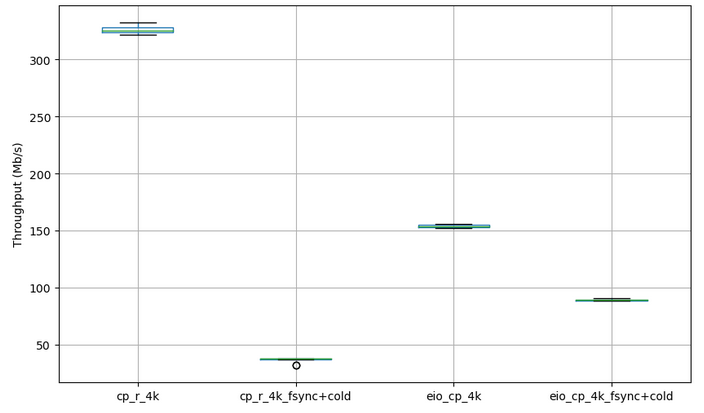

Benchmark 1

eio_cp against system cp -r with and without “fsync + cold cache”

Our results shows what we predicted, the eio version outperforms the sequential one under “fsync + cold cache” configuration because it makes blocking occur much more often.

Does that mean that if our workload benefits from having data in the page cache and/or does not need strict persistence guarantees, we should favour the sequential version? Well not quite. The filesystem we’ve been testing on has many small files, making it much more likely that data can be found in cache and each read/write returns quickly. Let’s see what happens when we increase the size of files to 1 MB

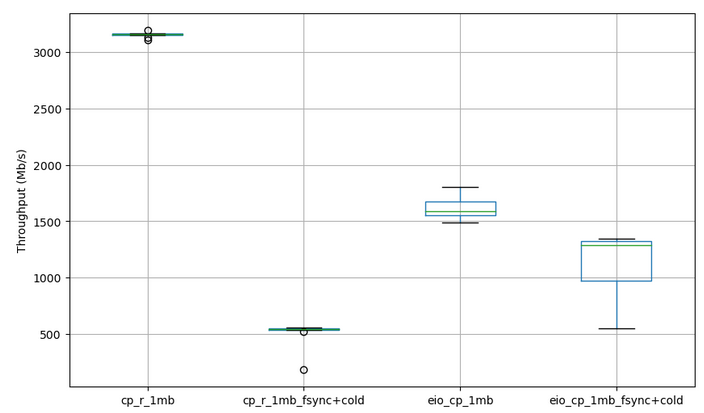

Benchmark 2

Our new test directory has the following structure:

Directory depth: 5

Files per directory: 4

Filesize: 1MB Num files: ... Total IO size = 780MB (R) + 780MB (W)

Num files: 780

Total IO size = 780MB (R) + 780MB (W) = 1560MB

Two things jump out at me. The first is that we’re noticing some incredibly fast speeds, way above our expectations! The second is that we are still behind the sequential version.

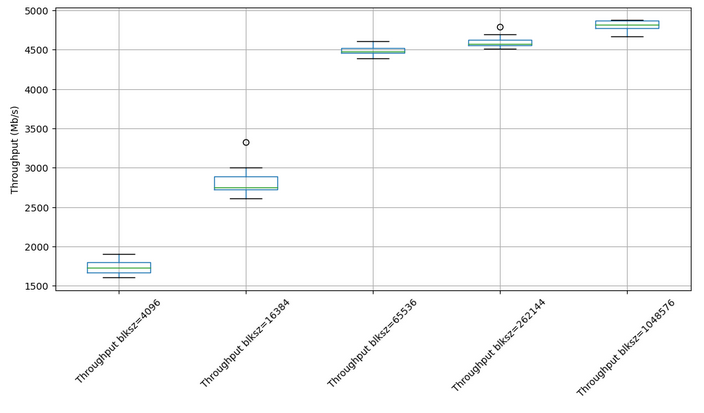

Initially I was puzzled by this result thinking that it was a bug in the benchmark suite. After looking over it several times, I finally figured out that it was because the workload change had rendered our theoretical expectations entirely inaccurate. Reconsidering our workload, copying many small files versus a few large is procedurally just much more stressful for disks even if the total size of IO is the same. In the small files case, the program has to do many iterations of opening, reading, writing. Hence, this pattern is synonymous with the random mixed read write speed we looked up earlier and is also the worst case scenario when it comes to disk performance. On the flip side, by increasing the size of the files, we’ve now altered this relationship to dealing with a much bigger block of sequential reads and writes. Updating our expectations we rerun the fio benchmark but now using a larger block size (The default previously was 4096).

fio --name=expect_upd_fsync+cold --rw=rw --size=1Gb --blocksize=1mi

--end_fsync=1 --invalidate=1

fio --name=expect_upd --rw=rw --size=1GB --blocksize=1mi --pre_read=1

That now seems to make sense but we haven’t figured out why the concurrent

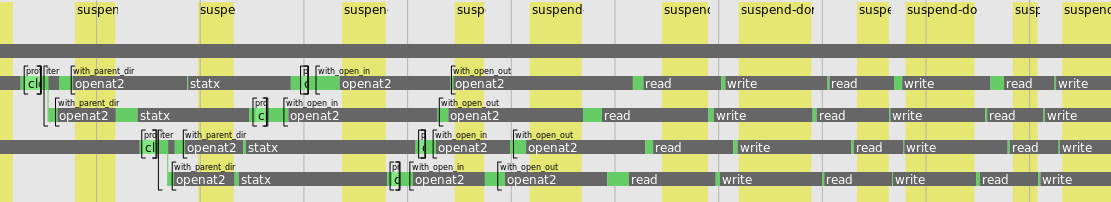

version still lags behind the sequential one. eio provides a useful

tracer eio-trace to visualize how fibers are interleaving in the

program. The trace produces

Hah! It looks like for every copy, there’s a long read/write loop.

Internally, eio uses 4096 Bytes as the default buffer size to copy between

files. This explains why copying a large file requires so many reads and

writes. Thankfully, the Eio_linux.run main function provides us an

option to configure this.

val run :

?queue_depth:int ->

?n_blocks:int ->

?block_size:int ->

?polling_timeout:int ->

?fallback:([`Msg of string] -> 'a) ->

(stdenv -> 'a) -> 'a

The main one of interest is ?block_size. Let’s graph the difference in

performance by varying the blocksize to see the effect.

Benchmark 3

Now that is a pretty substantial performance improvement! All with just

one tweak, though it took some real understanding to get here. So it’s not

always the case that the sequential version will fare better under

fsync+cold conditions.

Conclusion

That’s it! I hope that by stepping through this process, it has provided some useful context to help you think about adding concurrency for your filesystem workloads. Just remember that even if there are obvious opportunities to add concurrency, it’s not always going to provide you strict speedup. In all likelihood your OS is already doing something smart. Though having certain requirements or workloads could quickly tip the scales in favour of a concurrent approach.